Reducing the risks: Moving & handling and dementia across health and social care

and slings.

The purpose of this article is to consider, when carrying out moving and handling training, the following: Should we include how to deal with distressed behaviour for the person with dementia? We will explore person-centred strategies to improve the experience for the person being handled.

Is it an issue for the workforce?

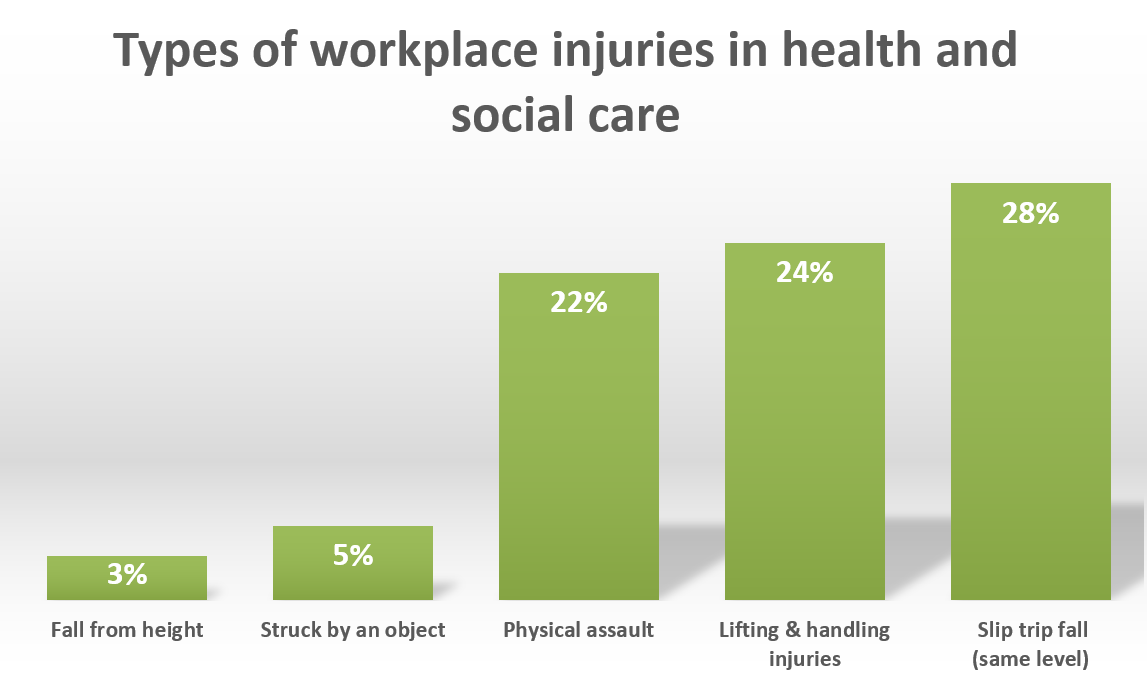

Moving and handling in the health and social care sector is recorded as the second largest reason for workplace injuries. It accounts for 24 percent of all reasons of employee injuries (HSE 2018), image 1.

The HSE (2018) identified moving and handling and physical assault in the health and social care sector as being the second and third highest reasons for workplace injuries respectively (see image 1).

The HSE recommends that employers should work with their employees towards creating a safe workplace to reduce these risks (HSE, 2019). It also acknowledges that there is an under-reporting culture, therefore it is estimated that the figures are higher.

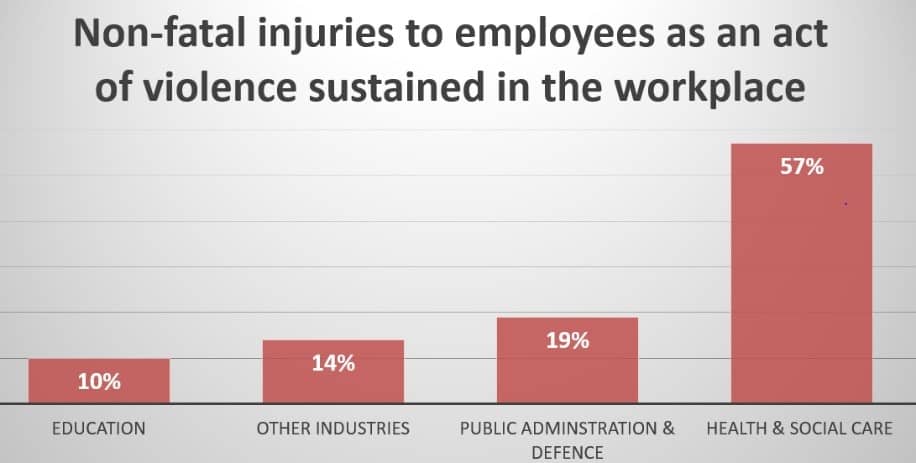

The health and social care sector is the industry that sustains the largest proportion of injuries due to violence in the workplace (see image 2) (Riddor, 2018).

Many of these will involve a range of service users in their home and patients in a hospital or community care setting.

One of the increasingly common client groups where physical assault occurs in the health and social care setting is those with dementia or learning disabilities. Therefore, if we can establish the cause of their distress, we will be able to reduce the amount of physical assaults in the workplace.

Would a combined approach to moving and handling training make a difference for the organisation that has a client group with dementia?

A workplace evaluation was carried out by Sturman (2018) alongside a combined approach to moving and handling to reduce the number of workplace injuries and work days lost. This demonstrated significant improvements across all areas when combining moving and handling and dementia training.

Combining trainng would also appeal to employers as a means of cost saving.

A competency assessment approach to moving and handling training was found to significantly improve the postures and skills whilst reducing the errors of the students (Webb and Harrison, 2019).

The use of video and safe systems of work to support moving and handling training was identified by Webb and Harrison as playing a significant factor in reducing risk and improving skill (Webb, Harrison and Szczepura, 2016).

If we combine the moving and handling and dementia training with a competency model and use of an online system, will this improve the outcomes for the person with dementia?

The issue of a growing elderly population is well documented, currently there are 850,000 people with dementia in the UK, with numbers predicted to rise to over 1 million by 2025. We need to have systems, equipment, training and strategies to effectively deal with this.

What is dementia?

Dementia is a word that describes a variety of symptoms that may include: an impairment of thinking; memory loss; difficulties with thinking, problem-solving or language; and, sometimes, changes in mood or behaviour. Dementia interferes with a person’s ability to do things which he or she previously was able to do. One of those important things is the deterioration in the person’s ability to mobilise.

“Moving and handling in the health and social care sector is recorded as the second largest reason for workplace injuries” Deborah Harrison

Dementia isn’t a natural part of ageing. It occurs when the brain is affected by a disease. There are many known causes of dementia, the most common types are Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia.

What are the symptoms?

In brief, everyone experiences dementia in their own way. There are some common symptoms: memory loss, difficulty planning, communication, being confused about time and place, visual difficulties, mood changes and mobility.

What are some of the behaviours we may see when someone is distressed?

We may see emotional outbursts, such as crying, shouting, shaking, mumbling, walking with purpose, rocking, restlessness, swearing, inappropriate sexual comments or hiding things. If you have ever cared for this client group you can identify some of the physical behaviours, such as: pushing away, grabbing, hitting, pinching, pulling hair and throwing things. When we see these behaviours, we can feel the emotion radiating from the person (Evans, 2019).

What are some of the causes and triggers for distressed behaviours?

An example is hypersensitivity to noise and certain tones in the environment, leaving individuals unable to decipher different noises. They may have a decline in vestibular function, which could, for instance, make them feel dizzy and disorientated.

They may have a visual disturbance; this can cause people to misunderstand or misinterpret something in their environment. A good example of this is the pattern of a carpet on the stairs.

Case Study

Doris has advanced dementia; staff are struggling to move and handle her. They have been hoisting her to carry out her transfers using a hoist and sling. Doris has become increasingly agitated, especially during the transfer from the bed to the chair. Doris appears sensitive to noise; she has been hitting out at staff and shouting when they have tried to hoist her. There are normally two staff to carry out the transfer.

Consider: What are the causes of Doris’ behaviours and possible solutions?

Is communication important?

Person-centred communication strategies are vital, consider how you would feel if you could not communicate, if you could not tell someone that you did not like a smell or if something was too loud. Or how would you feel if someone took something from you and you did not understand why? Imagine if you were in agonising pain and unable to express it.

Touch

This is a powerful stimulus and is often a way we communicate with each other. Sometimes touch is wanted and welcomed, and sometimes it is not. We have to consider the person’s preferences in this area.

Case study

Patricia became anxious when being turned from side to side in bed and would become very anxious when the carers came into the room. Patricia wept, grabbing at the carers and pinching them whilst they were trying to turn her. The carers became increasingly firm with their hand holds whilst moving and handling her, this resulted in bruises and an escalation of Patricia’s behaviours. Patricia actively resisted being turned. Patricia started to demonstrate other behaviours that were unrelated to moving and handling.

Consider: What are the causes of Patricia’s behaviours and possible solutions?

Assessment tools

Assessment tools for distressed behaviour have been available and are still current today (OSHAH, 2009).

“We do need to remember no one technique fits all” Deborah Harrison

We need to use tools to measure what is happening. It is that old chestnut: if we did not measure it, it did not happen and we have lost an opportunity to capture important data.

The purpose of collecting and summarising data is to observe trends, develop person-centred strategies and solutions, and reduce the behaviours that are just as distressing for the person and the handler.

A Behaviour Summary sheet (OSHAH, 2009)

- When did the behaviour occur: day of the week or weekend and time of day

- What behaviours were observed?

- Who was present?

- Where did the behaviours take place?

- What happened prior to the behaviours?

- What happened while the behaviour occurred?

- What interventions were used?

- What was the outcome?

- Were there any follow-up recommendations?

Using a format similar to this will enable you to observe any potential trends. Consider: is it just happening at the weekend, a specific time of the day, a particular task or with certain people? It can often be a long process of elimination.

One of the tools you may consider is the about-me passport for the person with dementia, the tool will move with the person as they transition across services.

Case Study Considerations for Doris

- If Doris is sensitive to noise, are the two care workers talking over her, vocally loud, banging about with other pieces of equipment?

- Is Doris startled when they first appear, do they need to gradually wake her up?

- Will Doris respond better with one carer? Can she be moved and handled easily with one carer with the right equipment and risk assessment?

- Is any of the equipment noisy?

- Is any of the equipment noisy due to the environment, such as the floor covering?

- Is it just the hoisting from the bed to the chair? Are the care staff taking the bed down and the hoist up at the same time? That would cause a vestibular disturbance with all of us. It is the same effect as sitting in the car and someone sets off at the side of you, it makes you feel as though you are rolling backwards.

- How does Doris like to be touched?

We do need to remember no one technique fits all. Consider your approach and communication styles, we will be covering this and other strategies in another article.

www.a1risksolutions.co.uk / 0161 327 2195

References

Alzheimers Society, The dementia guide-Living well after diagnosis https://www.alzheimers.org.uk/publications-about-dementia/the-dementia-guide (accessed 11 May 2019)

Evans, S. (2019) Preventing and responding to distressed behavior during sling fitting for individuals with dementia Naidex Conference 2019

OSHAH, (2009) Behaviour Documentation Toolkit http://www.phsa.ca/documents/occupational-health-safety/toolkitohsahbehaviourdocumentationtoolkit.pdf (Accessed 16 May 2019)

Health and Safety Executive (2018) Violence in health and social care http://www.hse.gov.uk/statistics/causinj/violence/work-related-violence-report-2018.pdf (accessed 11 May 2019)

Health and Safety Executive (2019) Violence in health and social care http://www.hse.gov.uk/healthservices/violence/ (accessed 11 May 2019)

Health and Safety Executive (2018). Work related musculo-skeletal disorders in Great Britain (WRMSDs) 2018. http://www.hse.gov.uk/statistics/causdis/msd.pdf (accessed 13 April 2019)

Health and Safety Executive (2018) Employer-reported non-fatal injuries by kind of accident and broad industry group (RIDDOR) www.hse.gov.uk/statistics/tables/ridkind.xlsx (accessed 11 05 2019)

Sturman. M (2018) Dementia – Reducing Distress (Caregivers and People) AAMPH Conference.

Webb, J. and Harrison, D. (2019) University of Salford : Moving and Handling Competency Passport ISBN: 978191233726 http://usir.salford.ac.uk/50116/ Accessed 16 May 2019

Webb, J., Harrison, D. and Szczepura, K. (2016) An online manual handling toolkit to improve skillls and reduce risks. Contemporary Ergonomics and Human Factors 2016 http://programme.exordo.com/ehf2016/ (Accessed 16 May 2019)